The un-told story of the Taman Bebek land dispute.

How a Supreme Court Ruling, Bali's Complex Social Fabric and Greed have Shaped the Battle Over One of Bali's Most Coveted Views, for 100 Years.

Want to help us on the next steps of Taman Bebek? Then let's unravel this real estate epic from the start.

You might want to catch up on previous updates for context:

- 1. Sacrifice to the Gods of Capital

- 2. The Countdown

- 3. The Crazy Wall

Before we start we wish to provide a brief disclaimer regarding the information presented below. The narrative that follows is a simplified account of the findings our legal teams have uncovered throughout 2024. The findings below were deliberately concealed and obscured from us over the years, creating a timely and challenging process to unravel the details of this land dispute that has persisted for nearly a century and we are finally understanding it. With this context in mind, we share our current status with you and as we move into 2025, we invite you, the Friends of Taman Bebek to be an active part of the next steps of this journey.

Because this is about more than Taman Bebek; it’s a call to protect an island whose unique essence is slipping away too quickly!

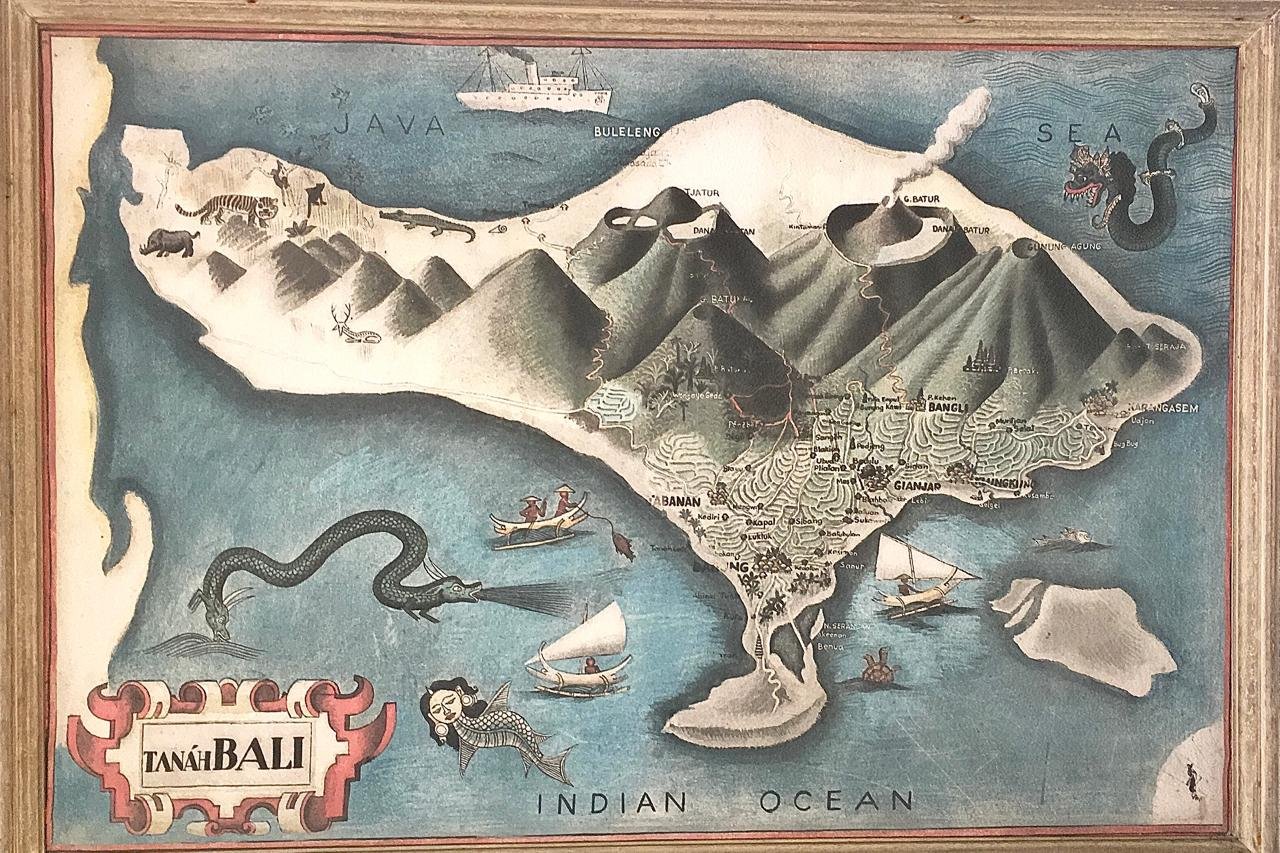

1932 - The Land Dispute Begins

This Land Dispute Over Ownership Began at the Court in the 1930s!

The property where Taman Bebek sits, was the first land in Sayan ever to be leased to a foreigner, the ethnomusicologist Colin McPhee, who years later wrote in his memories A House in Bali the saga of getting it leased. Colin McPhee wrote:

“I offered to lease the land for ten years, with a lease to drawn up legally before me Controlleur in Gianyar. But before this could be done, the pipil or deed would have to be found. This was a bit of writing scratched on palm leaf. No one had seen it for ages, and it took a month to find. In the meantime the village heard of the amazing news, and soon found out that Rendah would profit considerably. This was too much! A long and bitter dispute arose over the ownership of the land. The village claimed it had always been village property. Chokorda Rahi, the prince, suddenly appeared, all smiles, to say that the land belonged actually to him, had been given to him long ago by his father, in the palace at Ubud. The land had been merely loaned to Rendah, he claimed, adding sweetly that I was welcome to it, I must please accept it. Rendah, however, insisted that the land had been given outright to him by the Chokorda in return for money he had once loaned, and the day the pipil was found the Chokorda had to retreat, baffled. This pipil on examination turned out after all to be made out in favour of Rendah’s older brother, the klian, with items—the coconut trees remained the property of Chokorda Rahi; the crop was his; one-fifth of it went to Rendah in payment for watching the trees. At last it was agreed that the klian should receive the rent, while I would engage Rendah as gardener and watchman, and give him a similar amount. Both were pleased; this maintained a balance, was justice. The village, however, was far from pleased, and immediately began a lawsuit against the klian. Two months later the verdict was given at the Courthouse in Gianyar, and they had lost. Angry meetings now took place in the pavilion of the elders. Kesyur told me they had vowed to take the case to Buleléng; then to the Governor-General in Java, and later, if necessary, even to Queen Wilhemina herself in Holland. But Jacobs, the Controlleur in Gianyar, assured me the village had no claim, and that I could begin to build. I did not like the idea of breaking into a hostile community. “

Colin McPhee - “A House in Bali” -.

“The village, however, was far from pleased, and immediately began a lawsuit against the klian. Two months later the verdict was given at the Courthouse in Gianyar, and they had lost. Angry meetings now took place in the pavilion of the elders. Kesyur told me they had vowed to take the case to Buleléng; then to the Governor-General in Java, and later, if necessary, even to Queen Wilhemina herself in Holland. ”

— “A House in Bali” by Colin McPhee

1971 - The Land Is Transferred

Then in 1971 a Land Grant Set the Stage for a Legal Battle in the 2000s

Possibly inspired by the women's rights movement or the presence in Ubud of futurist thinkers such as Buckminster Fuller, the then title holder of the land grants the property ownership to a woman of his family, offering a glimpse into the progressive shifts of the time. But not everyone was happy with this decision…

Note: the land where Bucki Fuller built his geodesic dome in Ubud in the 1970s is for sale! Contact us if you are interested to know more.

1999 to 2001 - Price Spike & Supreme Court

The 1999 Land Price Surge Escalated the Dispute All the Way to the Supreme Court.

The land remained in dispute between the two landowners since the 1970s but as prices soared after Suharto’s fall, it prompted the rightful heirs to file a lawsuit and escale it to the supreme court, as their land was being registered by the local priest.

Finally, after various courts, the Indonesian Supreme Court upheld the rightful ownership of the property, resolving the longstanding legal dispute. The court confirmed the validity of a 1971 land grant (hibah), which had legally transferred the property to the plaintiff’s heirs. (No.: 2705 K / Pdt / 2001) 👉See full court ruling here.

The decision recognized the plaintiffs as the lawful owners of the land, rejecting the defendant’s attempts to claim it and obstruct the certification process. Prior rulings by the Gianyar District Court and the Denpasar High Court had already sided with the plaintiffs, and the Supreme Court’s rejection of the defendant’s cassation appeal solidified those judgments.

This decision marked a significant victory for fair land ownership and legal clarity in Sayan.

Until…

July 2024

The Post-Pandemic Land Rush Led to a Defiant Move Against the Supreme Court Ruling.

In a bold move backed by a foreign investor seeking to get hold of the land and influential institutional allies, the local priest made another attempt to register the disputed land—this time in direct defiance of the Supreme Court’s ruling and the land boundaries. The strategy proved successful, as the land certificate with newly defined boundaries was secured in 2024, without the leaseholders (us) knowing, giving new owners enough room to land grab and enclose Taman Bebek in a crazy wall. Remarkably, this was achieved without significant opposition from other Taman Bebek landlord who acceptingly saw part of his land taken away.

How is this possible?

well…

Late 2024.

Things started making sense.

Traditional Power Structures vs. National Legal Systems.

In Bali, social status, the intricate caste system, and the concept of "losing face" in the village play a significant role in shaping outcomes. In this case, the defendant, a local priest, openly defied the Supreme Court ruling, asserting his claim as the rightful owner of the disputed land. Backed by the village leadership and foreign financial support, he has become an insurmountable threat to the plaintiff, who in the past fought tirelessly to defend his land and his heirs' rights through the Gianyar Court, the Denpasar Court, and ultimately winning with a supreme court rule in 2001—only to face land grabbing again.

2025